A vast area of semi-desert stretches across northern Kenya into Ethiopia and Somalia. Life here is harsh for the area’s pastoral and semi-nomadic communities. Drought, lack of infrastructure, conflict over scarce resources, cattle-rustling and banditry are major challenges.

A vast area of semi-desert stretches across northern Kenya into Ethiopia and Somalia. Life here is harsh for the area’s pastoral and semi-nomadic communities. Drought, lack of infrastructure, conflict over scarce resources, cattle-rustling and banditry are major challenges.

Towards the end of last year, Joseph Karanja, a volunteer with Initiatives of Change, was asked by the Kenyan Government to join a helicopter mission to northern Kenya, specifically to show the documentary film An African Answer. 500 people affected by cattle-rustling conflicts watched the film.

Last week, the film’s director Alan Channer was invited to help develop a strategy for use of the film by the different communities of Baringo County and the remote area of East Pokot.

Twelve community leaders, representing the Tugen (a branch of Kalenjin), Njemps and Samburu communities, engaged in a three hour discussion after viewing the film.

Twelve community leaders, representing the Tugen (a branch of Kalenjin), Njemps and Samburu communities, engaged in a three hour discussion after viewing the film.

‘One entry point [to tackle our problems] is peace committees’ says Paul Keitany, a Catholic Justice and Peace Commissioner inspired by the film.

Many of the people in this town are IDPs [internally displaced people]’, explained Maryanne Ntausian, founder of the NGO Rural Women’s Development Network. ‘They are here because they have lost their cattle in raids.’

‘We need a new approach,’ urged one of the participants. ‘We need peace committees in our communities in order to discuss the issues that are affecting us – disparities in employment, grazing rights, cattle rustling. When Turkanas, Pokots, Njemps and Tugens can talk together about problems, we can generate local solutions.’

‘We need a new approach,’ urged one of the participants. ‘We need peace committees in our communities in order to discuss the issues that are affecting us – disparities in employment, grazing rights, cattle rustling. When Turkanas, Pokots, Njemps and Tugens can talk together about problems, we can generate local solutions.’

Another participant added: ‘We need a peace committee of women and a peace committee of youth from each community, as well as of men’.

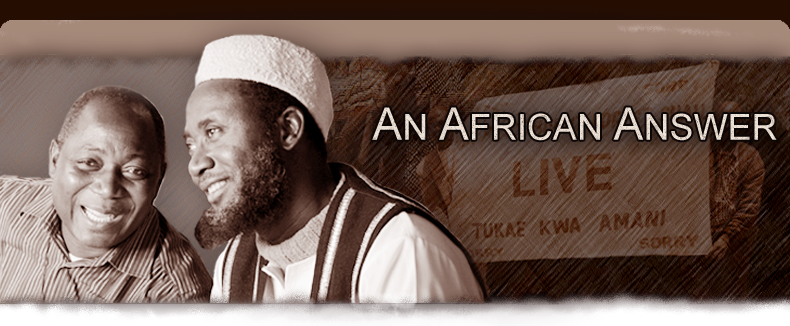

A head teacher was struck by the way in which former enemies Imam Muhammad Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye, depicted in the film, now work together to foster peace. ‘I was touched by this video. I have worked for seven years in Turkana. Can Turkana and Pokot be like the imam and the pastor? We need mobile film showings; we need peace ambassadors.’

A head teacher was struck by the way in which former enemies Imam Muhammad Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye, depicted in the film, now work together to foster peace. ‘I was touched by this video. I have worked for seven years in Turkana. Can Turkana and Pokot be like the imam and the pastor? We need mobile film showings; we need peace ambassadors.’

Issues of trust and integrity came to the fore in the discussion:

‘If you discover that this person from your community has stolen cattle, what would make you tell people from the other community?’

‘Who is it that is selling guns at the cheapest prices?’

Several participants commented on a scene in An African Answer where the conflicting parties write down their hurts and wrongs on pieces of paper and then burn these in a shared ritual of forgiveness:

‘We need to find the uniting factor. We need to start by slaughtering a goat together and sharing food together. We should live together in peace.’

After the screening, Keitany and Ntausian organized a fact-finding mission to three communities, to help develop a strategy for the use of An African Answer in the area.

After the screening, Keitany and Ntausian organized a fact-finding mission to three communities, to help develop a strategy for the use of An African Answer in the area.

A common thread emerged from the Kalenjin, Njems and Turkana communities visited. All were eager for peace and development; all also felt neglected by the government and other agencies. Each community had clear and unanimous solutions to better their lives. Empowering local solutions was another strand that the community leaders had responded to in the film.

Keitany concluded, ‘An African Answer is showing us the way forward. We need to take this message into the interior. That is my dream. It is a big challenge. With willingness, commitment and prayers, we will succeed.'